Homeless on Purpose: An Experiment in Travel and Working Remotely

Holy shit, I thought, I’m actually about to do this.

My heart was pounding. The room was dark. I wanted to sprint around the block or do pushups or scream — anything but sitting still in this moment.

I had told my friends about this plan. I’d even mentioned it to some colleagues. But now — staring at the computer, at the last step, ready to finalize everything — I was hesitant.

I felt The Fear creeping up my spine, wrapping around my throat.

This is where you find out if you’re a liar.

Deep breath. Self-assured nod to my imaginary audience.

I booked the ticket.

The Experiment: Live an Entire Year without a Home Address

If I imagine my perfect week, it’s built around travel.

I love exploring a new city, trying new food, meeting people with different backgrounds and perspectives, and learning about the culture and history of another corner of the world.

I also work remotely. This means — as long as there’s a decent wifi connection — I can do my job from anywhere.

I don’t want to take my situation for granted, so I’m ready for a new adventure.

The lease on my apartment in Portland expires at the end of this year, and I’m not going to renew it. I won’t be taking on a new lease, either.

Instead, I’ll spend the holidays this year selling off everything I own and putting a few things I can’t bear to part with into a small storage unit.

Then, on December 30, 2014, I board a one-way flight to Milan, Italy, with the intention of wandering around Europe, living month-to-month in places I’ll rent on Airbnb. The primary objective of this trip is to spend a full year living and working abroad.

What I Hope to Accomplish by Spending a Full Year Outside the US

There are myriad reasons I want to take this trip. At the root of it all, more or less, is my interest in learning what I’m made of — a rite of passage, so to speak.

In addition to my general curiosity about whether or not I can handle it, I’ve also made a lot of big claims to my friends and family.1 This trip is a way for me to test these hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: We Don’t Have to Wait Until We Retire to Travel

Since I travel often, a lot of conversations over drinks end up centering around travel. And for the people who like the idea of travel, I tend to hear a lot of the same reasoning for why they don’t do enough of it:

“I’d love to travel, but it’s just too hard with how busy I am. I’m planning to do a lot of traveling once I retire, though.”

I’ve never been a big fan of this line of reasoning. Why should I have to wait until I’m 65 to start doing the things I want to do? I don’t think it’s necessary to wait until retirement to start enjoying life and knocking items off my bucket list.

Waiting for retirement is a gamble, and I’m not sure I want to take the risks.

For example — let’s get morbid for a second — you might die before you ever reach retirement. And the idea of deferring happiness to a future you may not live to enjoy2 is just about the saddest thing I can imagine.

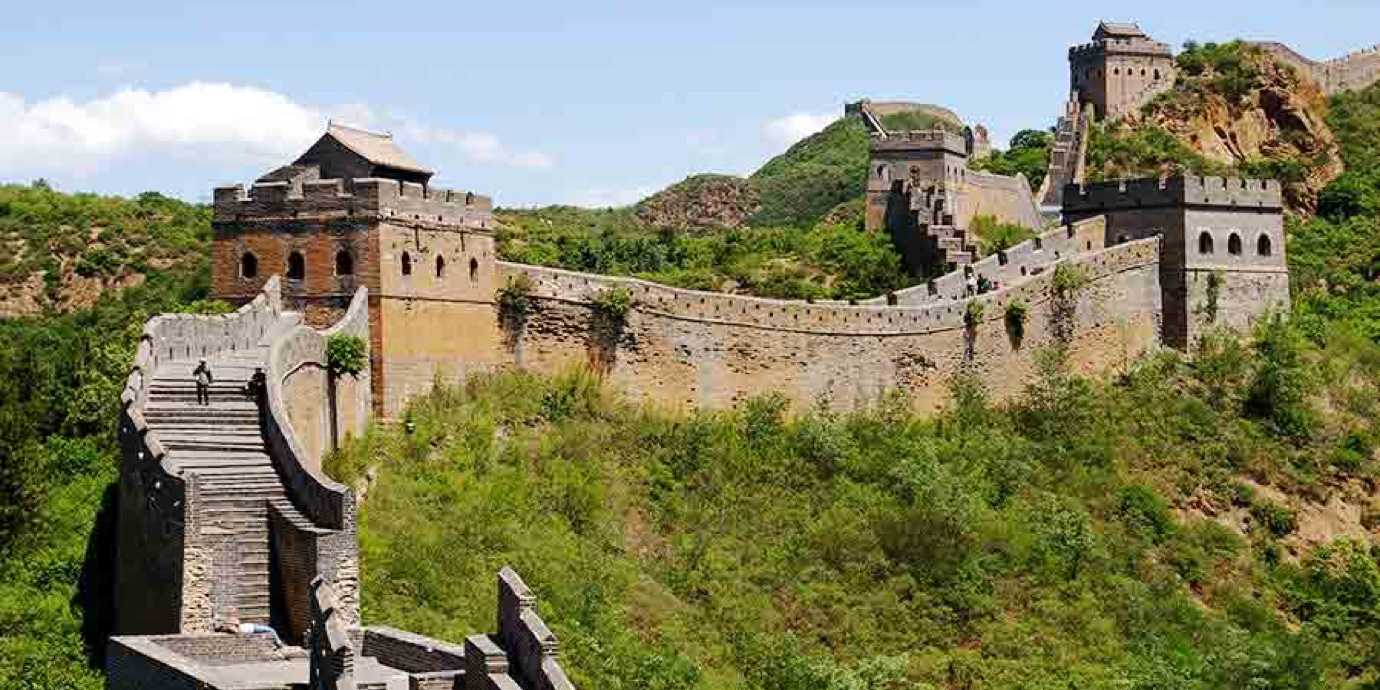

There’s also that whole problem with getting older: if your bucket list includes physically taxing adventures — like walking the Great Wall of China or running with the bulls in Spain — there’s a reasonably good chance your 70-year-old self won’t be up to the task and you’ll just… never do that.

I don’t have the same goals I had ten years ago.3 I don’t want to place bets that the guy I’ll be 35 years in the future will still want the things I want today.

I may not always want to learn to surf in Costa Rica. But I want that now, and I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t go out and do it.

Hypothesis 2: It’s Possible to Be Productive During Sustained Periods of Travel

Can I manage to stay productive while constantly exploring new places? I aim to find out.

In the past, I’ve seen a steep drop-off in productivity when I travel. I have a big list of things I want to explore, and a limited amount of time in which to do the exploring.

On a vacation, this is fine: I shouldn’t be working on my vacation anyways. But if the idea is to be traveling semi-permanently, it becomes a much bigger issue if I’m not getting anything done.

Through my work speaking at conferences, I’ve learned to block out my time and get things done without locking myself in a hotel room and missing the whole point of travel.

What I’m hoping to do with this year abroad is to refine my approach to work-life balance, figure out the minimum amount of hours required to meet my productivity goals, and spend the rest of the time out in these new places guilt-free.

Hypothesis 3: It’s Just as Cheap (or Cheaper) to Live Abroad

Let’s do a quick math problem: how much is your rent?

Now add your utilities. Cable. Internet. Renter’s insurance. Do you have a cleaning service? Add that.

The sum of all those bills is what you’re actually paying to live where you live.

Now go look at all the places on Airbnb that cost less than that per month. And remember: Airbnb includes the wifi, cable, and utilities.

Without any other changes in lifestyle, it should cost me less overall to rent apartments month-to-month overseas than I pay right now to live in Portland.4

Hypothesis 4: It’s Healthier to Live Abroad than It Is to Live in the US

First, let me remind everyone that I am not a scientist, a dietician, a fitness pro, or any other form of expert on the subject of health, so let’s make sure we’re all taking this with a grain of salt, okay?

I believe I will be healthier just by living in Europe instead of the US.

To start, I know that I will be walking more while I’m there. I probably won’t have time to get a driver’s license in many of the countries I visit, and I don’t necessarily want to spend a fortune on taxis. This will mean a lot of walking and public transit.5

Additionally, a lot of the terrible, fake shit that ends up in food in the US — stuff like artificial coloring and synthetic hormones — is outright illegal in Europe. Plus, even though it’s not banned, there’s a lot less high fructose corn syrup in food over there.

At the risk of sounding a little woo woo about it all, I’m pretty convinced that I’ll be eating healthier in Europe without making any changes to my diet, simply because the food is made from, y’know, food.

Hypothesis 5: Living Abroad for an Extended Period of Time Means Big Tax Breaks

This is the one I’m least certain about. However, as far as I’m capable of comprehending the US tax code, it should be possible — and perfectly legal — to claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion, which basically means that I don’t pay income tax on any money I make during the year.

Here’s my understanding of how this works: if I don’t have a home in the US and I’m outside the United States for a minimum of 330 days in a 12-month period, I can claim the exclusion. That means up to roughly $100,000 of income becomes tax-deductible.

The deduction exists because income tax pays for a lot of infrastructure — healthcare and emergency services, highways, and such — that I won’t be in the country to use, and therefore won’t be paying for while I’m gone.

So if I make the full hundred grand, I could save nearly $25,000 in taxes.

I know. Holy shit, right?

There’s a requirement that your “tax home” needs to be in a foreign country, but for those of us who are working remotely, that’s not an issue because we don’t have a “main place of business”:

If you have neither a regular or main place of business nor a place where you regularly live, you are considered an itinerant and your tax home is wherever you work. Excerpt from “Tax Home in a Foreign Country”

The only other thing I was worried about is that my employer, Copter Labs, is A) my company, and B) based in the United States. But this line from the tax code seems to imply that’s not an issue:

Foreign earned income is income you receive for performing personal services in a foreign country. […] For example, income you receive for work done in France is income from a foreign source even if the income is paid directly to your bank account in the United States and your employer is located in New York City. Excerpt from “What Is Foreign Earned Income”

I’m still wary that there will be a gotcha in the tax code somewhere, but I’m cautiously optimistic that I will be able to claim the Foreign Earned Income Tax Exclusion for every penny I make in 2015.6

[UPDATE — December 31, 2014] After consulting with Steve Barkley (my accountant) and Roz at Tax Warriors (an incredibly generous accountant who helped me out with research in her spare time), I’m now 100% certain that I’m interpreting the tax law correctly, and that I won’t pay federal income tax as long as I meet the requirements laid out above.

However, I did find out that state taxes aren’t set up the same way. Oregon, for example, doesn’t consider your residency terminated until you’ve established a permanent residence elsewhere, and they’re apparently pretty aggressive about collecting. If you’re considering taking a similar move, it would be wise to plan ahead and establish residency in a state without income tax.

Part of getting ready to leave, in my case, included changing my address to my parents’ place in Washington. They’re receiving my mail while I’m away, and if anything happens to me I’d like to be returned to my parents. Plus, when I do return to the United States when this whole thing is over, I’ll be moving in with my folks for a bit while I reestablish myself.

This, of course, has the additional benefit of making me a Washington resident. Before leaving, I got a WA driver’s license and registered to vote. The tax benefits, while certainly not unappreciated, are a secondary bonus to knowing that — should something bad happen to me — my address on record will put me at my dad’s front door.

I Will Sink or Swim in Public

I gave a lot of thought to whether I should talk about this before I left, or if I should wait until 2016 and post a recap (or, if everything failed, just do nothing).

I’ve decided that I want to give the most honest account I can of learning how to be an expatriate. In order to do that, I need to write about the things I’m thinking as I’m thinking them — if I come back and do a “here’s what I learned” post, it’ll skew the details because I’ll be writing from a place where I know the answers.

Right now I don’t know how this will work. I might find out six weeks in that I really, really hate not having my own apartment and just bail altogether. I might be horribly mistaken about how much it will cost me to live abroad, and I’ll have to come back to the US with my tail tucked to avoid bankruptcy. I might get audited by the IRS and end up totally screwed.

Because I don’t actually know how this will all go down, this post is naïve in a lot of ways. I’ll look at it in the future and cringe.

“What a fool I was!” I’ll cry to the heavens.

I want to collect all of the ignorance and obstacles I’m facing, and the subsequent realizations and strategies to overcome those obstacles. I want to document the path from zero to “I can hang”.

And at the end, I hope to have compiled a reference manual that will help me succeed as a remote worker and vagabond. (And you, if you’re into taking the plunge.)

Or, at the very least, I’ll have a charming story about that one time I went to tax jail.

P.S. If you want to follow along as I go on this adventure, make sure to subscribe for updates so new posts go straight to your inbox.

And anyone who was unfortunate enough to ask, “So what’s next for you?”

Especially if you’re a cop.

Some of my goals — doing projects for Fortune 500 companies, getting strong enough to do bodyweight chin-ups — were met. Others — working as a touring musician, building the next hot app startup company — just don’t match up with what I want anymore.

Portland isn’t even all that expensive a place to live; for those living somewhere like San Francisco or Manhattan, the difference could be huge. If you’re living in Montana, though, this probably doesn’t hold true for you; I still fantasize about my $600/month, two-bedroom apartment in Missoula.

I’ve already seen the benefit of walking: I got rid of my car earlier this year and started walking a lot more around Portland. Since February, I’ve lost 30 lbs. I’ve done other things beyond just walking more, but the walking certainly didn’t hurt.

I’m not entirely convinced this will actually work, so I’m going to keep all the money for taxes in a separate account that I won’t touch until I get confirmation from the IRS that I didn’t screw anything up.

What to do next.

If you’re like me, the idea of traveling permanently while making a living probably seems like a dream — but you don’t think you can pull it off.

I felt that way right up until I actually boarded a flight to leave the United States back in 2014 — and now I can’t believe I didn’t start living this life sooner.

The secret to a life on your terms — work where and when you want, living anywhere in the world — is remote work. And there’s good news: it’s easier than ever before to join the ranks of location-independent workers around the world.

I want to help you. The best remote workers all have a set of non-technical skills, and I’ve put together a free 6-point checklist to help you master them — and ultimately master your time and ability to work anywhere in the world.